In 1911, The British decided to shift their capital from Calcutta, Bengal to Delhi. In 1905 there was a controversial partitioning in Bengal due to the right to vote between Bengali Hindus and Muslims. The British therefore felt a political need to rearticulate their power. Delhi was identified as the perfect location for the move as it centrally located in northern India and had a historic significance in the previous empires as well. On December 15, 1911 the foundation stone was laid by King George V, under a ‘Shah Jahani’ Dome to express the power of the British empire just as Shah Jahan had laid authority of the Mughals.

Delhi as a site as was untouched at the time so the whole city could be planned from scratch. In Delhi, the site of the Raisana hill was selected so that the Viceroy’s House could be higher than the rest of the city as a symbol of power and majesty. The contours were mapped and sent to London so that the architects could then draft the plans for the new buildings. The contract was given to Sir Edwin Lutyens, who was known for his English country houses, and his friend Sir Herbert Baker, who was known for the government buildings in South Africa. Networking is Everything, A phrase all of us are familiar with, could never have proved to be truer than in the case of Delhi. Sir Edwin Lutyen’s was awarded the opportunity because he was in fact the son in law of Lord Lytton, the first viceroy of India!

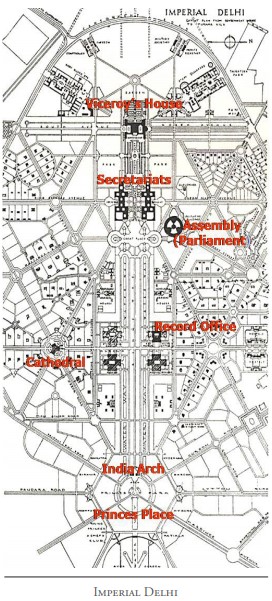

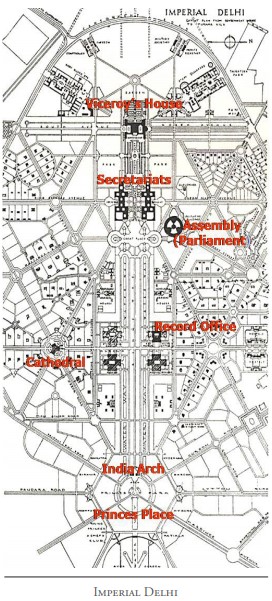

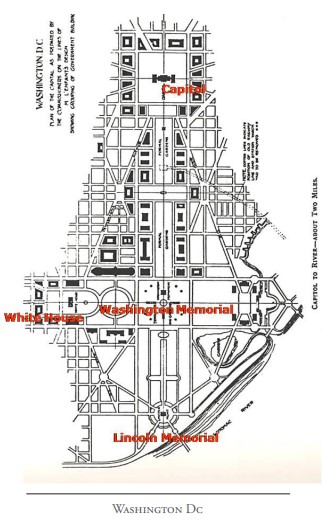

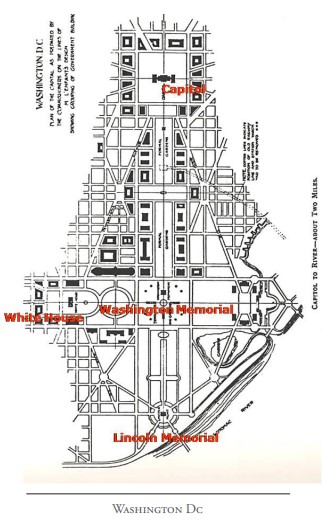

Lutyen’s was in charge of the Delhi masterplan. His initial design was complete with streets crossing each other at right angles just like the streets of New York. Upon seeing the plans, Lord Hardinge informed him of the prevailing winds and the dust storms that sweep the landlocked city of Delhi. Hardinge gave Lutyens the plans of Rome, Paris and Washington according to which Lutyen’s designed the Imperial city that we know and love today. From right angles, the plan changed into triangles and hexagons. The roundabouts, hedges and trees are not only aesthetic elements but also help to break the force of the winds.

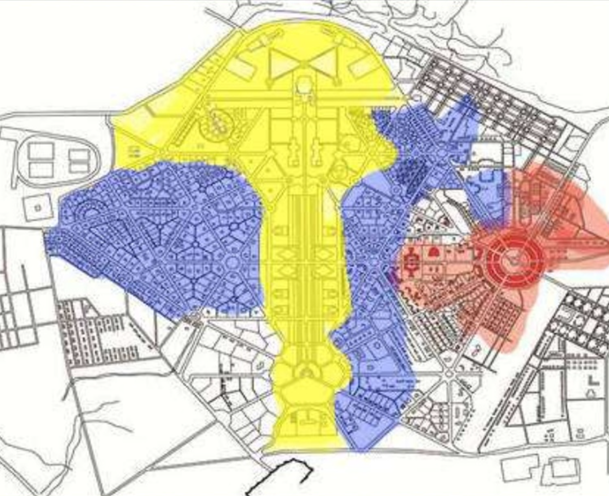

With a vision to include all natural and historical wonders, the layout of Lutyen’s Delhi has three main visual corridors to link the government complex with; Jama Madjid, Indraprastha and Safdarjung’s Tomb. Lutyen’s plan also includes green spaces, lawns, water courses and trees which are integrated with the parks developed around the monuments. This was inspired by the ‘Garden City Movement’ prevalent at the time. Even the tree planting was done according to specific principles such as symmetry, shade along avenues, hierarchy, etc.

The planning is done in such a way that the government complex is at the heart in the centre, the residential zone for the British is around it and then there is the commercial district, known as Connaught Place, and Old Delhi. The government complex is around a main ceremonial axis of the Rajpath (directly translated as the King’s Way). This was crowned by The India Gate on one side and The Rashtrapati Bhavan, or the Viceroy’s House, on the other side. This is called the central vista. On either side of this vista are the north and south blocks of the secretariat building and the Jan Path (literally translated to the people’s path) cuts across this axis to connect to the commercial district of Connaught Place.

Lutyen’s designed the Bungalow Zone which were residences allocated to British officials and their families. Each bungalow follows a G+1 typology so that no building height dominates the tree height. Greenery and privacy seemed to be the biggest factor as no two houses could even see their neighbors. Sprawling lawns around the building ensured that the residences were far apart and interestingly, the ground coverage of the built up area was only a mere 7%.

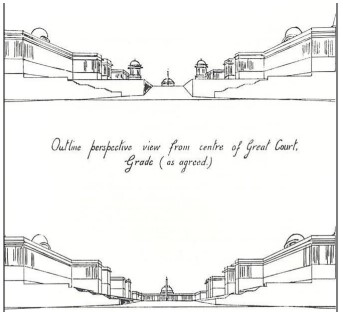

The controversy arose when it was time to design the buildings. Many wanted to follow the ‘Western Style’ while others argued that the style must take into account the history of Delhi. It is said that both Lutyen’s and Baker had no regards for the Indian sentiment and left to them, they would have transplanted the Whitehall to Delhi. It was Lord Hardinge, once again, who came to the rescue. He convinced them that it was not the British but the Indian public that they were designing this new city for. He insisted that they find a balance between the western and the Hindu styles and create a broader style. It is then that Lutyen’s designed the building we know today in the Indo-Saracenic Style. Built with indigenous materials, of pink and red sandstone, by Indian labor, the building includes multiple Indian elements. Jalis, chattri’s and chajja’s adorn the building and a Buddhist dome stands proudly at the top.

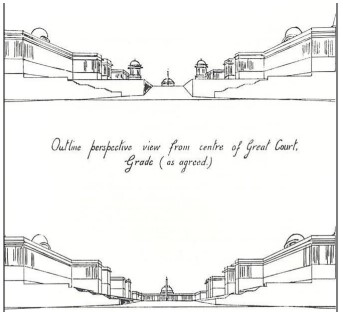

Many architects believe that the Viceroy house was planned in such a way that when you are approaching the building from the ‘RajPath’ or King’s Way, you see the Viceroy’s House sitting high and mighty at the top. But connections only get you so far! When Lutyen’s came to visit after the construction had started, he realized that due to clerical errors in the contour drawings, the position of the building according to actual coordinates was different from the ones he had received. The building is actually behind the hill, instead of on top, so from the King’s Way you only see its crown! His vision was actually an unsuccessful one and with architecture of that scale, you only get one chance.